Helping Children After Natural Disasters

We had a different newsletter just about ready to go this week, but the devastating news out of Texas inspired me to put out this post first. For those of us with a connection to summer camps, Texas, SAR teams, other natural disasters, or who have or work with kids or faith communities … this all hits extra close to home. I attended a webinar July 10 with trauma psychologist and disaster survivor Dr. Jamie Aten on How to Help Kids Cope with Crisis, which was particularly for those who may be supporting children in light of the recent Guadalupe River flooding. It was a poignant reminder of the power of spiritual first aid and community connection.

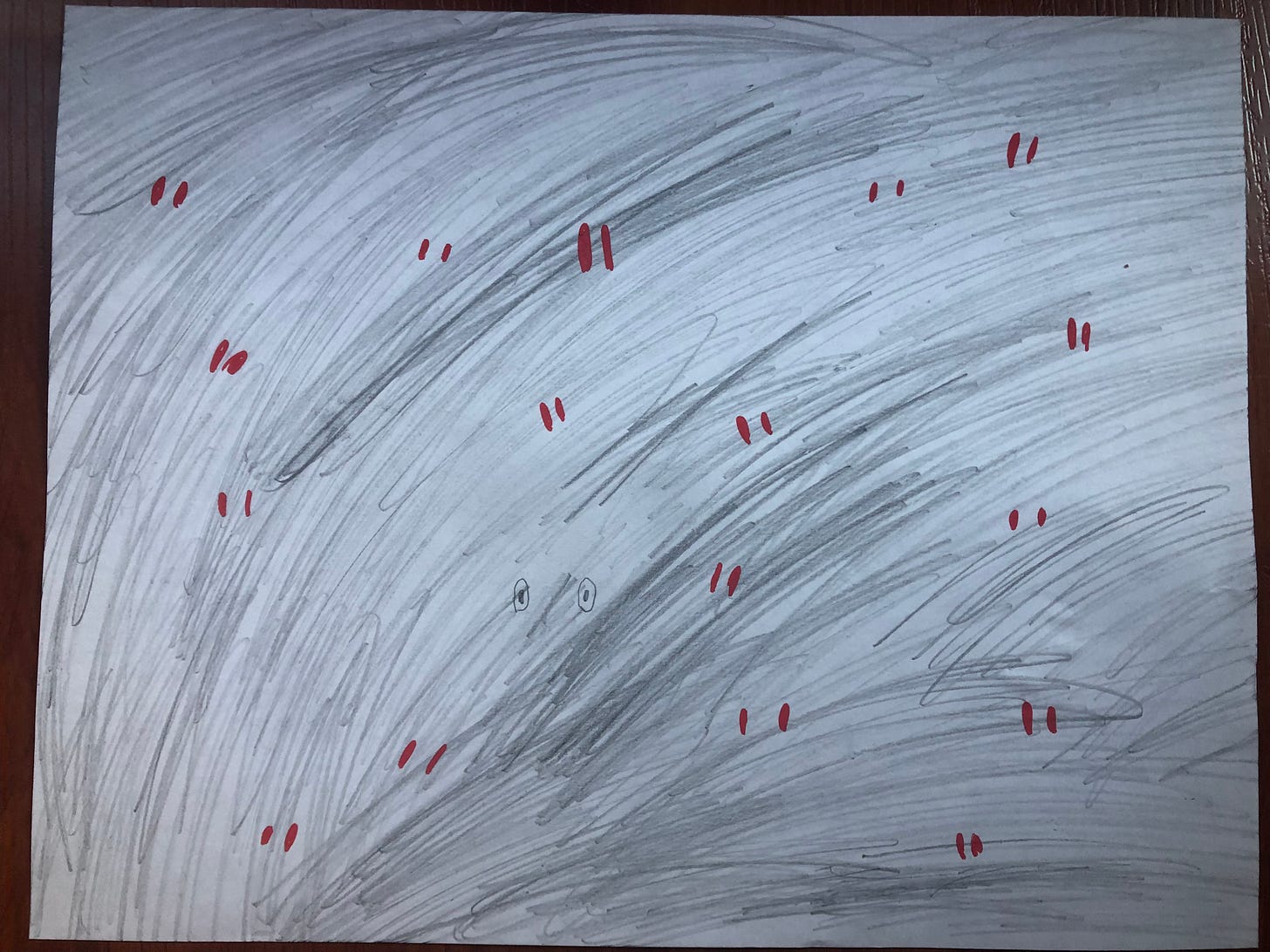

Among the images Dr. Aten shared that I most appreciated was this one:

It’s a reminder that sometimes the adrenaline and the shock in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy may “keep us going” in the acute response time — meaning, the darkest emotional days will likely come after that initial impact or “honeymoon” period of support has passed. If you have someone in your life who has experienced a tragedy or disaster, consider reaching out again a few months later. Bring a “belated” meal. Send a “still thinking of you” card. Connection is the correction.

If you’d like to help, Mental Health Wilderness First Aid is matching donations to the Texas Search and Rescue fundraiser, up to $1,000. We’re low-tech over here, so just send us a screenshot of your receipt and we’ll pop on and match your donation until July 20th.

We’re organizing our newsletter on Substack now — a platform that seems to lend itself better to longer-form writing (which I’m still doing all myself, with no input from AI, thanks!). We’ll continue sending occasional newsletters to everyone on our mailing list, however longer-form articles like this one will be an extra offering for paid subscribers going forward. Today’s is a freebie: See below for ideas for supporting young children who have experienced natural disaster or other trauma exposure, including points from a talk I gave for survivors of the Colorado Marshall Fires in 2022.

All the best,

Daye Hagel, MHWFA Director

Supporting Children

Children can indeed be affected by traumatic experiences, even if they’re too young to “remember”. Although children’s conscious or “Wizard Brains” are underdeveloped, meaning they may indeed be too young to have encoded a conscious or explicit memory of an event; their unconscious “Lizard Brains” are fully formed, and that is the part of the brain that encodes trauma responses!

In addition to other trauma symptoms, children may experience trouble concentrating at school, anxiety, clinginess, aggression, nightmares, or regressive behaviour (e.g. return to bedwetting after previously being fully toilet trained). Trauma in children is sometimes missed as it can look like learning disorders, ADHD, deliberate defiance, depression, simple sleep or eating disturbances, withdrawal, or other mental health issues.

The good news is, children also have the capacity for resilience. As grownups, we can help children to access this and process their experiences in a healthy way. Here are some things to consider.

Set an example and access our own support

As the people who are likely the most in contact with the children in our families or communities, it is important for us to access our own support networks and take care of our own needs for stability and security. Reach out for support. We can also set an example for children about how we are thinking and feeling about an event that occurred. While very strong adult trauma responses may frighten or unsettle a child, it is healthy for children to see adults express their feelings and thoughts in ways that are compatible with their safety. “That was a really terrible thing that happened to our family. I still feel scared and cry sometimes, and when I do I like to talk to someone about my feelings, or I say a prayer. Even though it’s still hard, it helps me feel a little better.”

Re-establish routine

It is natural for routines to be disrupted during a crisis. As soon as practical, re-establish stability by getting children back in to a familiar (or a newly-familiar) routine: when we get up, what and when we eat (eating together helps), school or playgroup, bedtime routine. This predictability is a form of rhythm that helps children’s (and adults’) brains to re-attune to safety and to regulate. Rules and expectations are stabilizing. As Dr. Aten says in the webinar I linked above, “Tell your kids, ‘You still have to do your chores’.”

Include children where reasonable

Look for ways to include children in ceremonies, funerals, vigils, age-appropriate discussions, and even solicit their opinions regarding decisions that concern them. This provides opportunities for children to connect, process, and heal.

Provide psychoeducation

Teach children about how our brain works when it’s stressed, in an age-appropriate way. Give kids language to describe what they are experiencing: Lizard Brain and Wizard Brain can be helpful metaphors for children (as well as adults), including how they respond when we are threatened, and how to help the Lizard when it is actually safe but over-acting. (We practice offering psychoeducation and regulation strategies in the MHWFA 16h Basic course.)

Assure children they are cared for and this was not their fault

Children who have experienced trauma have experienced not being protected in ways that they should have been protected, and may take on inappropriate “caretaker” roles, for themselves or for other children or adults. Children are also sometimes prone to “magical thinking,” and may attribute cause to their own actions or thoughts. Did I cause the fire because I wished something bad would happen when I was angry?

Even if they have not voiced these concerns out loud, children need to hear from a caring parent or other grownup, “It’s grownups’ jobs to take care of kids. Here is what we are doing to keep you safe going forward: …” and “Did you know that this was not your fault? There was nothing you did that caused this.”

Support play

Play is the natural healing language of children. Children process, understand, & heal through repetitive play. This is particularly true because for young children, especially for those who have experienced trauma, the logical and conversational parts of their brains are not fully developed yet. They may not (likely do not) have the language to express what happened to them, and to process it cognitively. Play, on the other hand, is a beautiful, instinctual form of processing that is accessible and healing to all.

Your child’s play may develop themes of:

Danger, despair, hiding, or running

Being rescued or rescuing

Superheroes and supervillains

Death and/or resurrection

“Regressive play”, e.g. earlier developmental stages, “playing baby,” wanting to be rocked, cuddled, or soothed.

As long as they are not really hurting anyone, play, even play with serious themes, can be healing for children. It is also okay to indulge children in some extra soothing, cuddling, rocking, co-sleeping, or “playing baby”, if they are initiating that. Their little limbic systems may just need that extra reassurance and experience of being cared for and protected, like they were at a younger age. As they heal, the regressive behaviour is likely to extinguish over time. So, encourage children to play! Play with them, follow their lead, and allow them to explore themes through to their conclusion.

Knowing what we do about the naturally soothing activities for the limbic system, you can also encourage “relational, rhythmic, repetitive” activities together, especially:

Rocking, patting, hugging (especially for very young or pre-verbal little ones)

Singing, drumming, music, dancing

Walking, paddling, bicycling

Tapping (see Jain’s Tapping for Zapping book in the recommended children’s books resource below).

Playing catch or ball … or tossing your socks around.

“Look for the helpers”

Mr. Rogers, host of the Mister Rogers’ Neighbourhood show from 1968-2001, had a wonderful teaching for grownups about when children are witness to terrible things in real life or on the news. “Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are trying to help.” This is a type of cognitive intervention for children and adults alike.

Guide children to actively identify and focus their attention on who helped in a scary situation. Do you remember when the ambulance showed up? Who is helping the people who are trapped? (Try it out: if you were looking at the artwork done by Huck Stevens above, what is one thing in the picture you could draw both of your attention to?).

Although we should take care not to imply that children are responsible for safety or for outcomes, you can also help children to feel empowered by remembering small ways they were or are able to help. (Feeling helpless is one of the contributing factors to developing PTSD, and focusing on action can help to mitigate that effect). “Do you remember how you helped by calling for Daddy when it was time to go?” Or, “Even though it was scary for all of us, your little sister stayed calm because you held her hand and sang a song with her. I really appreciate that and I want you to know.” Or, “The Andersons lost a lot of their toys in the accident. Do you think we could try to help them?”

Connect to Resources

Some counsellors (myself included) specialize in “Expressive Play Therapy,” for working with children who have experienced grief or trauma. In my experience, play therapy with young children tends to be effective only in person; however, if there is not a practitioner in your area, you could also consider consulting with a trauma-informed play therapy practitioner over Zoom, about how you as a parent or caregiver can support your own child through something called “child centered play” or even “filial therapy”.

The Lumara Society is an excellent organization that runs online and in-person programs to support families and individuals who are facing death, grief, or serious illness.

Support your child connecting with his or her own community in regular, predictable, and fun ways. Set playdates, get outside, get involved in groups, churches, sports, and clubs. Connection is the Correction!

See Daye’s list of recommended children’s books on mental health topics.

The preceding was adapted from an excerpt from the MHWFA Manual, version 2.6. Order a copy of the MHWFA Manual in print or PDF form. (A free PDF copy of the Manual is included with annual Substack subscriptions.)

Upcoming Courses

Basic "101" Course (16h)

Build powerful mental health awareness, assessments, tools and skills that you can put to use immediately in your workplace, family, or community. No experience necessary.

September 15, 17, 22, & 24, 2025 (Mon & Weds evenings)

October 4 & 11 (Saturdays)

November 5, 12, 19, & 26 (Wednesday evenings)

Upgrade from Basic to 40h+ Course

Build on your Basic skills with in-depth discussions on supporting people with mood disorders, trauma / PTSD, disordered eating, psychosis, grief and loss, self-harm, and suicidal thoughts, all through a lens of resilience.

December 3, 6, 10, & 13, 2025 (Weds & Saturdays)